Enacted in 1967, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”) was, in part, an outgrowth of the civil rights movement. Congress had been informed that age discrimination occurred not because of any dislike or animus towards older workers, as is the case with other forms of discrimination, but because of “inaccurate stereotypes about older workers’ declining abilities and productivity.” It therefore enacted the ADEA with the stated purpose of promoting “employment of older persons based on their ability rather than age; [prohibiting] arbitrary age discrimination in employment; [and helping] employers and workers find ways of meeting problems arising from the impact of age on employment.”

Broadly speaking, the ADEA makes it unlawful to refuse to hire, discharge, or otherwise discriminate against an employee or potential employee over 40 years old on the basis of age. That includes a prohibition on issuance of any employment-related advertisement indicating a preference based upon age. Job notices may not contain terms that discourage older workers by containing statements “such as age 25 to 35, young, college student, recent college graduate, boy, girl, or others of a similar nature” unless an exception applies.

Recently, three named plaintiffs commenced a potentially extremely large class action lawsuit against T-Mobile, Amazon, Cox Communications, Cox Media Group, and others (including 1,000 “John Doe” companies) alleging violations of this prohibition. According to their Amended Complaint, the named defendants and others each advertised job positions on Facebook that “routinely exclude older workers from receiving their employment and recruiting ads,” thus denying those individuals an employment opportunity.

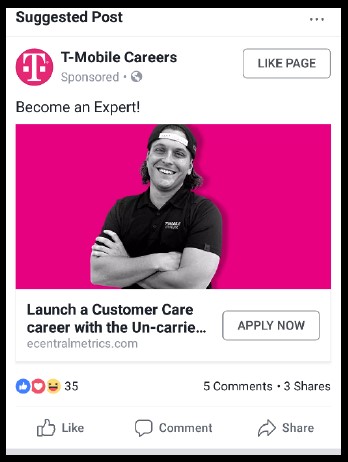

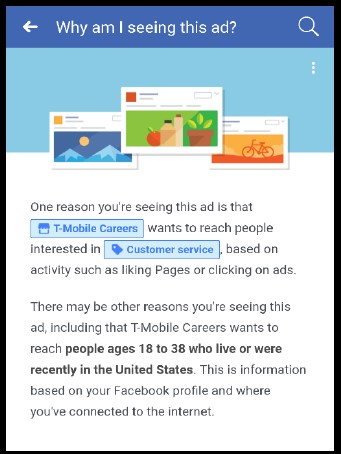

Specifically, Facebook permits companies advertising on the platform to choose who they wish to advertise to using a number of criteria, including age. Targeted advertisements are nothing new, of course. But, given the nature of social media and Facebook’s business model and the information provided by users, companies can advertise with extremely accurate criteria. According to the plaintiff’s Amended Complaint, one such advertisement used by T-Mobile looked like this:

When a user checks to see why they are receiving this advertisement, however, they are told as follows:

The Amended Complaint names a number of other companies as potential defendants, including Capital One, Sleep Number Corp., and IKEA. It seeks certification of a class of plaintiffs, believed to be in the millions, and made up of Facebook users over 40 years of age. The Amended Complaint alleges claims under the ADEA and similar state statutes.

It will be some time before this litigation is concluded. Based upon statements in the media, it would appear that the defending companies are pursuing numerous defense strategies, including comparing these advertisements to place similar ads in magazines or other print materials targeted at a younger audience. Settlements in cases of this size are quite common, and so the litigation may never require a Court to fully consider whether the claims are legally valid.

In the interim, however, the case offers another reminder to employers using social media to do so carefully. Although most companies are more comfortable with the changing media landscape than they were ten, or even just five, years ago, the legal fallout of that change continues.

This information is general in nature and should not be construed for tax or legal advice.